A Deeper Dive into Longi's Wafer Advantage

Gauging the durability of Longi’s moat against the ever-changing solar technology landscape

My first write-up on Longi Green Energy described how the Company used its advantage in monocrystalline wafer production to become the world’s leading solar module manufacturer, but it was a little light on the technical details. I do think it’s possible to get comfortable with a position in Longi without a deep understanding of solar technology, based on simple factors such as its leading vertical integration and scale, its relative financial strength, and its owner-operator management team with an excellent track record of making shrewd capital allocation decisions and delivering value to shareholders. However, this may not be enough to convince the professional skeptics who subscribe to this newsletter.

This article will attempt to answer a few burning questions. How sustainable is Longi’s technological moat? If the last shift to a more efficient type of solar cell left incumbents vulnerable to rapid decline, will future shifts threaten Longi’s competitive position? Should we instead be looking for the next Longi, by figuring out who will lead the next big wave in solar technology?

Solar Cell Composition

All solar cells consist of multiple layers of materials that work together to convert sunlight to electricity, and all single-junction solar cells have the same basic structure, regardless of the materials used. The top antireflection layer traps light and promotes its transmission to the energy-conversion layers below. There are three energy-conversion layers: a top junction layer, an absorber layer, and a back junction layer. The absorber layer is made from a semiconductor material that can absorb electromagnetic radiation at the wavelengths of visible light, such as silicon. When light hits the absorber layer, electrons become excited. The junction layers create an electric field that allows the electrons to flow to the electrical contact layers and into an external circuit.

There are many different types of solar cells, but they all fall into three broad categories: crystalline silicon, thin-film, and emerging PV. Crystalline silicon (c-Si) cells are the most common with a 95% share of the market thanks to a winning combination of cost, durability, and efficiency, the ratio of solar energy that is converted to electricity. Thin-film cells are cheaper as they use less material, but they lack the efficiency to compete effectively with silicon. The emerging PV category includes a number of different semiconductor materials and structures that enable cells with higher efficiencies than silicon alone, but they are too expensive for terrestrial applications to date and can only be found in a laboratory setting or in outer space. Each cell type has a theoretical efficiency limit determined by the physical properties of the cell materials, and actual efficiencies have increased over time as production processes are improved. However, it is important to note that there is a significant gap between efficiency observed in a laboratory setting and the efficiency that can be achieved economically at scale; it can take nearly 30 years for the industry to catch up to efficiencies achieved at the research level.

As PV module costs decline in proportion to the entire system cost, efficiency gains become an increasingly important factor in reducing a solar system’s LCOE (Levelized Cost of Electricity). Realized crystalline silicon solar cell efficiencies steadily increased over the past decade as the mainstream Al-BSF(Aluminum Back Surface Field) method was displaced by the more efficient PERC (Passivated Emitter Rear Contact) method. PERC cells improve light capture by adding a passivation layer of silicon nitride and alumina to the back of conventional cells that allows light to be reflected off the back surface into the cell again. PERC technology increases efficiency by about 1% to 1.7% for roughly the same cost of production. The technique is more effective with higher-purity monocrystalline cells, which contributed to the widening gap between monocrystalline and polycrystalline cell efficiency:

Monocrystalline cells are more efficient than polycrystalline cells because they are cut from a single source of silicon, whereas polycrystalline cells are blended from multiple silicon sources. Polycrystalline cells were once mainstream due to their lower cost, but Longi led the industry transition to monocrystalline cells by dramatically reducing the cost of two key processes, RCZ technology for ingot pulling and diamond wire cutting technology for wafer production.

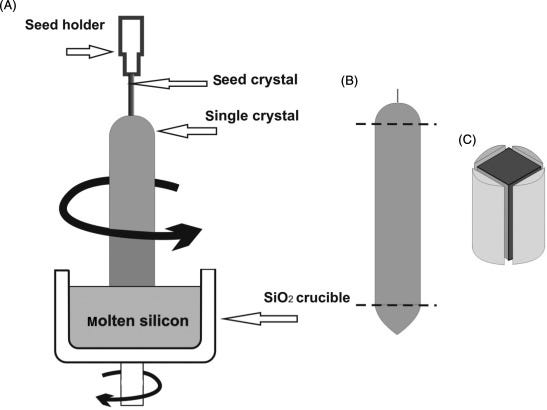

In the CZ (Czochralski) method for creating silicon ingots, a seed is dipped into molten silicon, which is then slowly raised as it is rotated. The original CZ method only allowed for one ingot per crucible, as the crucible could not be reused due to cooling and cracking after pulling. The RCZ (rechargeable Czochralski) method greatly improved productivity by allowing for reloading the crucible through a feeding device while maintaining the temperature of the crucible, enabling multiple ingot pulls from a single crucible. Longi has reportedly increased crucible utilization from one ingot to nine today, thanks to hundreds of small iterative improvements to the process. Through independent research and collaboration with Linton Crystal Technologies to design customized furnaces, Longi’s crucibles and ingots are also getting larger over time with no signs of slowing down:

Diamond wire cutting was first developed in Switzerland and Japan, but Longi was the first company to localize and widely deploy the technology in China. The process is 4 to 5 times faster than the traditional slurry cutting method and enables thinner wafers with less waste and a higher cell yield. The localization of equipment and consumables reduced the price of diamond wire from the original 500 RMB/km to less than 50RMB/km. Initially, the diamond wire cutting method was less effective for polycrystalline wafers, as the diamond wire left a smooth texture that was incompatible with existing production processes. This required wafer and cell makers to make adjustments that resulted in fewer cost savings, further narrowing the cost gap between monocrystalline and polycrystalline wafer production. In large part due to the adoption of diamond wire cutting, Longi’s cost of monocrystalline wafer slicing has fallen more than 80% since 2011.

The combination of a narrowing gap in production cost and a widening gap in efficiency drove a very rapid industry transition from polycrystalline to monocrystalline silicon wafers. Longi launched to number one while incumbent industry leader GCL-Poly stumbled badly, weighed down by a massive investment in stranded assets that could not be converted to monocrystalline production. As previously discussed in my first post, technology S-curves can be very difficult for analysts to anticipate, even when they are right in the middle of one. See this gem from November 2018:

It is obvious that mono is gaining on multi and becoming the more widely used technology, but analysts and market participants are divided as to how far this will go. “We are not so bullish as the other voices in the market,” states IHS Markit’s Edurne Zoco. “The market is not going to be 80% mono in two years.”

Narrator: Two years later, the market was 90% mono:

The industry has reached a consensus around the advantages of monocrystalline silicon wafers, and there is no technology on the horizon that would facilitate a return to polycrystalline. As all surviving firms have now turned their attention to monocrystalline cells, Longi has gone from competing with itself to make monocrystalline economically viable to competing with the entire industry to maintain its pole position. This is a common pattern with innovative disruption and has been observed in many other industries. Tesla is a great example, which toiled alone on electric vehicles for years until the value proposition was such that it became clear to all players in the automotive industry that they would need to enter the EV market in order to survive. Despite the proliferation of new EV models in recent years, Tesla’s growth has accelerated and profitability has surged.

How can you catch up with a winner who is already running full speed when you are starting the race years behind? Most of the time, you can’t. Major technological disruptions can leave the door open for a potential change of guard, but these chances are rare. While the solar industry does move a lot faster than most, the anticipated technology shifts over the next decade are incremental changes in doping, wafer size, module layout, and materials used in other layers, with monocrystalline silicon expected to continue to be the core absorber material. Incremental changes can create opportunities for new equipment makers to emerge as new fabs and tools are required, but Longi’s ability to deliver industry-leading efficiency in upcoming formats suggests there won’t be too much of a shake-up amongst the integrated module makers.

The bigger concern for Longi is what will happen as silicon cells approach their theoretical efficiency limit about a decade from now. A class of materials called perovskites has emerged as the most likely successor to silicon, as they are cheap to produce, easy to manufacture, can achieve higher theoretical efficiencies than silicon, and have rapidly improved realized efficiencies at laboratory scale, from 3.8% in 2009 to 25.7% in 2021. However, matching the durability of silicon (with 20-25 year standard warranties) is still a major challenge that could take decades for perovskite cells to overcome at commercial scale. In the meantime, tandem cells using both silicon and perovskite as absorber layers will likely reach commercialization after 2025, and they will likely displace single-junction silicon cells over time with a significantly higher theoretical efficiency limit of 45%.

There is currently no way to invest directly in perovskite’s potential via the public markets. Oxford PV is one of a handful of private companies focused on perovskite, with a pilot production line for tandem cells launching in 2022 and a multi-junction perovskite cell under development. I would flag this as a very promising technology to monitor, but at this stage in the technology’s development, its impact on silicon PV growth is negligible.

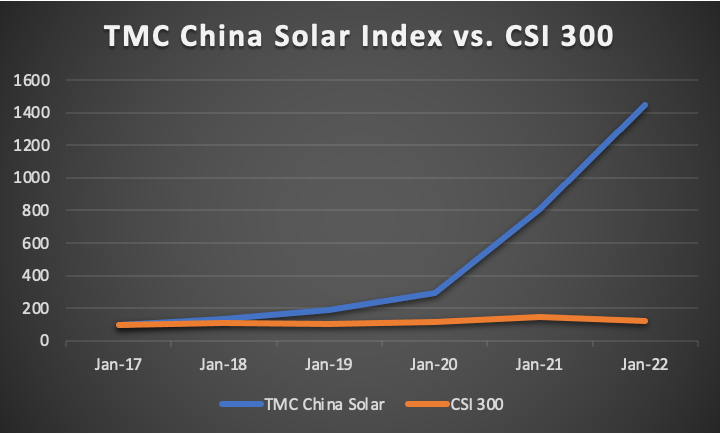

The new era of solar grid parity presents a massive growth opportunity for companies that are delivering commercial products now. As the industry ramps up production, there will be more demand for specialized equipment, materials, and complementary products. Most of the quality companies in the supply chain are listed on the Mainland Chinese exchanges. In the coming weeks, I will share details of a custom index I have created that will track what I believe to be the most attractive opportunities in the industry. On average, the group is expected to double earnings over the next two years and trades at about 20x 2024E earnings.

This index was constructed with the benefit of hindsight, and past performance is no indicator of future results. However, I think we will find future winners here by looking for strong moats and rapid earnings growth at a reasonable price.