Longi Green Energy: The Sun Rises in the East

Longi has grown from humble beginnings to become the undisputed global leader in the solar industry, and there's still a long way to go

601012 Longi Green Energy Technology

Market Cap: CNY406 billion (US$60 billion)

Note: Longi shares split 1.4:1 today, so information in financial databases may not be accurate.

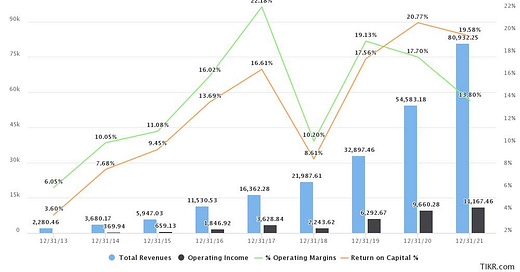

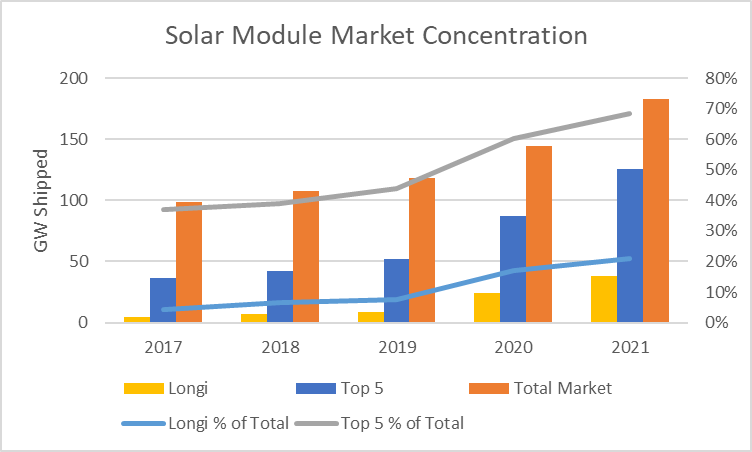

Longi Green Energy Technology is the world’s largest solar module producer, shipping 50% more GW than its nearest competitors in 2021 to hold approximately 20% market share. This is a fairly recent development, as Longi only first entered the module market in 2014 through the acquisition of a relatively minor player and gradually rose through the ranks to take the top spot in 2020. Over the last five years, the Company has grown revenue and earnings at a 40%+ CAGR, driving 55% annualized returns for shareholders.

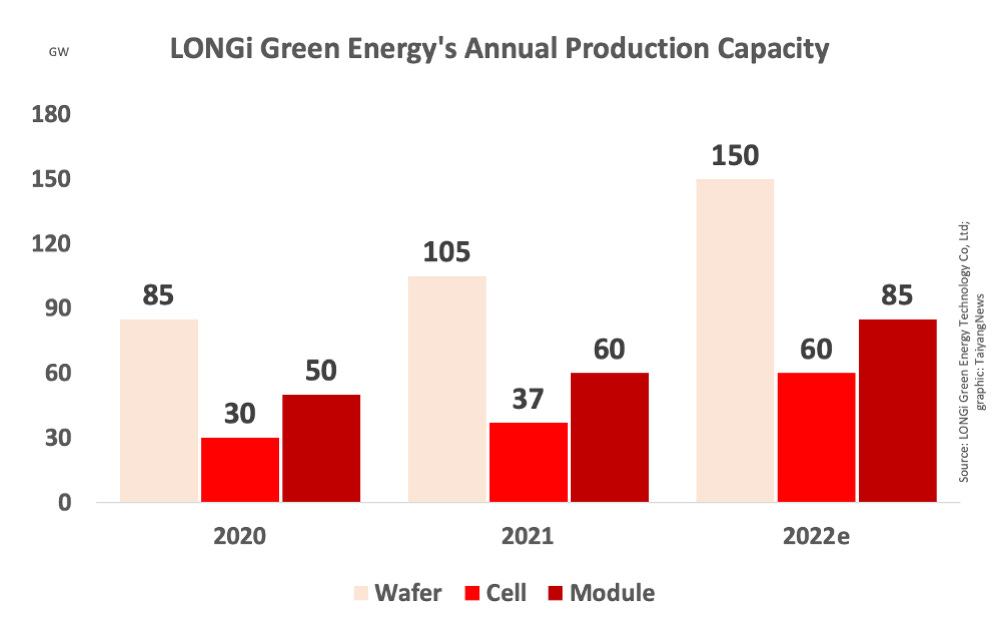

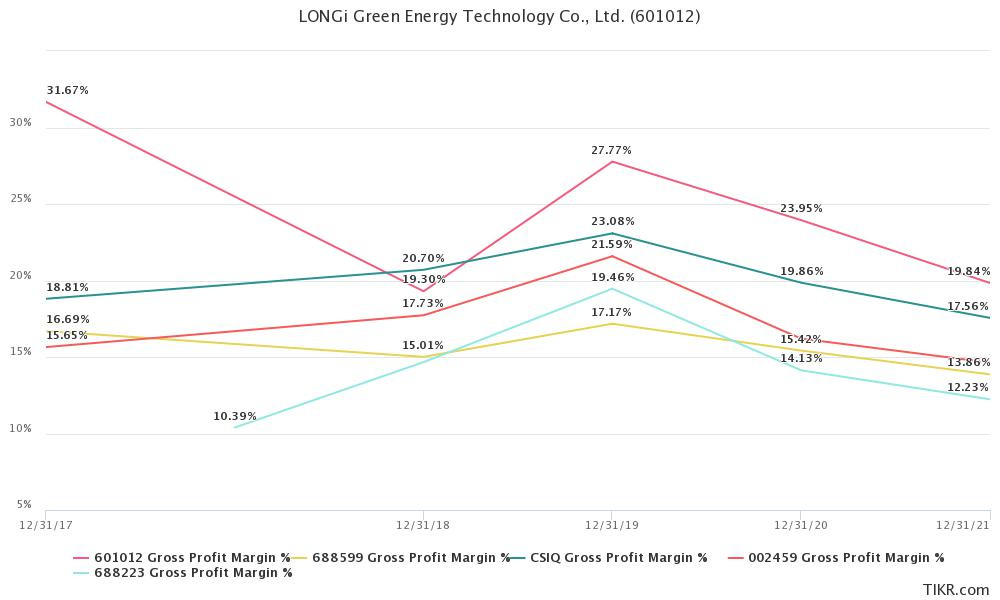

In 2021, Longi recorded twice as much revenue as its nearest competitors at significantly higher operating margins (14% vs. 5-8%) and ROIC (20% vs. 5-10%). Longi generated roughly as much operating income in 2021 as the rest of the top ten module manufacturers combined. In a hyper-competitive industry with a history of financial instability, Longi has emerged as the only AAA-rated module supplier according to PV-Tech. Longi achieved this by first dominating the monocrystalline silicon wafer market, where it has captured a 45% share, and then moving downstream into cells (cut wafers) and modules (assembled cells). As a result, Longi’s module competitors are often reliant on Longi for their key inputs, which constrains their growth and margins while Longi is in a better position to scale their downstream operations, especially during periods of turbulence across the supply chain. After increasing module shipments by 55% to 38GW in 2021, the Company has planned for another year of strong growth to deliver up to 60GW of modules in 2022:

The Company’s focus on monocrystalline silicon has paid off as the industry has almost entirely flipped from polycrystalline silicon since 2014. The monocrystalline cell manufacturing process is more expensive, as cells are cut from a single crystalline silicon ingot, whereas polycrystalline solar cells are blended together from multiple pieces of silicon. However, the pure composition of the monocrystalline cells enables higher efficiency and better performance in suboptimal conditions (high heat, lower light). As a result, monocrystalline modules command a higher price per watt.

In addition to enjoying cost and scale advantages from vertical integration, Longi is also a leader in the large-scale commercialization of PV technologies that enable higher conversion efficiencies and lower rates of decay over time, resulting in a higher price per watt. Ongoing research from the Company’s R&D team frequently churns out new records in efficiency from various new cell technologies which could be scaled up in the future. One example of successful commercialization is the Company’s leading position in bifacial technology, which increases module efficiency by capturing reflected light off the ground with PERC cells.

Bifacial Technology. Longi 2020 Investor Presentation

Longi’s advantages in vertical integration, scale, and technology translate into a significant advantage in financial performance over peers (Trina, JA, Jinko, and Canadian Solar). Over the past five years, Longi has registered the highest returns on invested capital, higher gross margins, and industry-leading operating costs as a percentage of revenues, resulting in the highest operating margins in the industry:

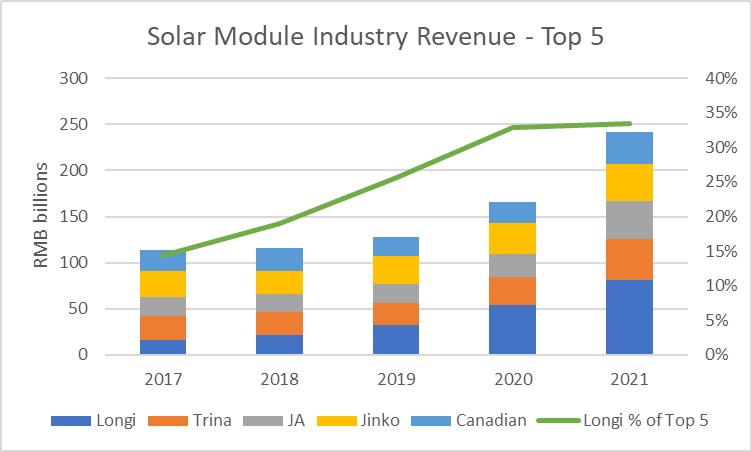

Longi is pressing its financial advantage, growing revenue at a faster clip than the other vertically integrated module manufacturers and gaining share while capturing a significant share of the industry’s profit:

The vertically integrated module manufacturers are rapidly consolidating the market due to better control over cost and a more stable supply of material inputs, led by Longi:

2030 Forecast

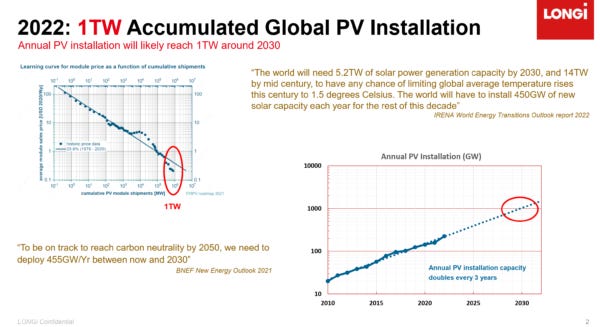

Over the past four years, on average Longi has added 36% of the industry’s incremental annual capacity. It appears that Longi’s dominant competitive position will allow it to take at least 33% of the total module market in the long run, with a superior margin profile that will enable the Company to capture more than half of the industry’s operating profit. The more difficult question for investors to answer is just how large the solar module market will be in 10-20 years in dollar terms. The module makers themselves are expecting global annual solar deployment to hit 1TW by 2030, which would far exceed mainstream estimates (BloombergNEF: 334GW, IEA: 630GW) despite being in line with the long-term trend.

In this scenario, the market would grow more than 5x from here in terms of annual deployments. However, the historical learning rate of about 20% for solar modules with each doubling of installed PV capacity would reduce the growth in industry revenue to a bit over 3x. If Longi continues to deliver more than a third of the industry’s incremental annual deployments, its revenue could grow by roughly 5x by 2030. If Longi’s net margins came in on the low end of its 5-year range between 11% and 16%, the stock today is trading at about 8x 2030 earnings, with an earnings CAGR in the high teens. In the near term, analysts are expecting Longi to register another year of strong revenue growth of 40%+ in 2022, with growth then moderating below historical norms in 2023 and 2024. At roughly 28x this year's earnings and 22x 2023 earnings, the stock is trading roughly in line with its 5-yr average NTM P/E ratio. This may look expensive in contrast to the S&P Energy forward P/E of 10x or Saudi Aramco’s forward P/E of 15x, but Longi’s fortunes are not tied to volatile commodity prices as it is a manufacturer rather than a producer. Vertically integrated manufacturers of renewable technology, with low fixed costs and high gross margins to weather any challenges with input costs or output prices that affect their entire industry, will ultimately emerge as long-term winners in the ongoing energy transition.

If this is the base case (and projections of a steep drop-off in annual deployments the bear case), the bull case would be stronger than expected pricing over the next decade, higher industry margins as concentration increases, and the potential for Longi to use its financial strength and market dominance upstream to gain more market share.

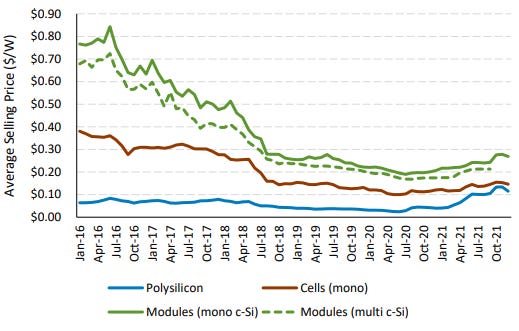

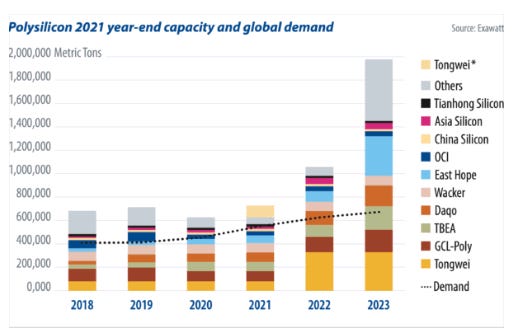

Recent developments bring into question the assumption that prices will continue to fall as rapidly as they have in the past. Average monocrystalline module prices increased by 50% in 2021 and currently sit at levels last seen in early 2018. This is primarily due to surging commodity prices, in particular polysilicon, the raw feedstock for silicon ingots and wafers, which has roughly tripled over the last two years. Cost declines that naturally come from scale and process improvements have been canceled out by rising material input costs. With raw materials now comprising about 70% of solar module costs, it is very difficult for module manufacturers to avoid passing these rising costs on to end customers:

PV Value Chain Spot Pricing, NREL

The encouraging development here, at least from the standpoint of the module manufacturers, is that annual deployment growth is accelerating in spite of higher prices, from 9% in 2018 to 27% in 2021. There are two plausible explanations for this. One, the industry is becoming more consolidated, as the top 5 module manufacturers have grown from 37% of the market in 2017 to 69% of the market in 2021, and as industry concentration rises, there should naturally be less price competition (see DRAM industry revenue and operating margins over time as the number of significant players declined from 20+ to 3). Two, prices do not need to fall much further for newly built solar to be cheaper than operating most fossil fuel plants, especially if oil, gas, and coal prices remain elevated at current levels. While solar module prices have returned to 2018 levels, the price of oil has doubled, the price of natural gas has tripled, and the price of coal has quadrupled. The challenge is no longer to cut costs and prices low enough to find enough demand to meet supply; the challenge now is to ramp supply enough to meet the current level of pent-up demand at current prices. Polysilicon prices will likely ease as a slew of new production capacity comes online this year and next, but the impact on module prices could be muted this time around with a greater sense of urgency from governments to address energy security (Germany’s response to Ukraine invasion and climate change (recent Australian election).

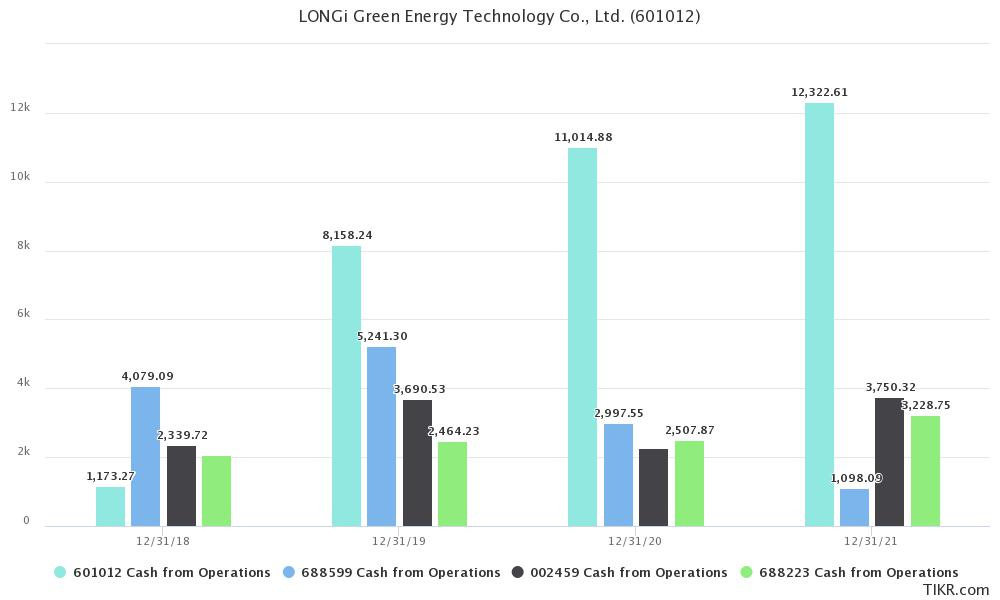

Longi has the potential to capture more than 33% market share in the long run. The Company could use a higher proportion of its monocrystalline wafer capacity (where it has ~45% share) for its own cells and modules, while monocrystalline could totally dominate the solar market vs. the less efficient polycrystalline (monocrystalline share has grown from 66% in 2019 to 84% today). This would give Longi 40%+ solar module market share. Longi is the only module manufacturer in a financial position to fund such an expansion from operations. Longi generated significant FCF while ramping operations over the past several years, while its nearest competitors have dipped into the red to keep pace. While smaller players are already being left behind as the market consolidates, at some point Longi’s major competitors may determine that it is financially unsustainable to protect their own market share and scale back on expansion, leaving more of the market for Longi. Financial strength is also important to customers, who may need to make warranty claims up to 25 years from the date of purchase, and Longi increasingly stands out as the safest firm to do business with.

Corporate Governance

Many investors are highly skeptical of Chinese companies, with good cause. Early on in my own investment journey, I researched hundreds of Chinese companies listing in the U.S. markets via reverse mergers with OTC shells. I visited fake factories, heard lots of tall tales from management, and witnessed hundreds of millions of dollars from foreign investors flow into these companies and simply vanish. There is a fairly obvious agency problem with many Chinese companies listed abroad, including Hong Kong; as China has no extradition treaty with the U.S. or most of the developed world, nothing happens to the managers inside China who successfully defraud investors in foreign markets. If anything, their illicit gains without consequence encourage more “entrepreneurs” to try their luck with another enticing story. Investors may wise up to obvious patterns and avoid certain promoters or auditors or listing methods, but it seems to keep coming around and around again to the point where no structure outside of China is bulletproof.

My main takeaway from that early experience was to not waste too much time studying businesses that were listed in the wrong market. If a Chinese businessman defrauds Chinese investors, there are at least some consequences. An angry mob might show up at his door, or he could serve life in prison. The ideal way to invest in Chinese companies is alongside Chinese investors in China, where at least you know you are aligned with locals looking out for their own interests. For a long time, the barriers for foreigners to invest in the Mainland markets were very high, but the introduction of the Hong Kong Stock Connect gave foreign retail investors a relatively easy way to participate. There is a strong push from the government to bring legitimate and strategically important companies listed abroad back home. Ironically, all of the real Chinese solar companies that were once listed in the U.S. and have now migrated to Shanghai and Shenzhen(Trina, JA Solar, Jinko Solar) had terrible financials at the time, reporting numbers that nobody would want to fake! Longi has always been listed in its home market, debuting on the Shanghai exchange in 2012.

There are many SOEs listed on the mainland exchanges, and it is fairly common to find a connection to the government in the ownership tables or at the Board level. This is not necessarily a bad thing in China; for example, China’s leading liquor brand, Kweichow Moutai, is majority-owned by a Guizhou government entity, yet minority shareholders have enjoyed 33% annualized returns over the past 17 years. As renewable energy and electric vehicles are critical industries to China’s long-term success, Longi is certainly benefiting from a favorable policy environment in China. But Longi is not an SOE; it was founded by semiconductor engineer Li Zhenguo, his wife, and his university classmates as a supplier of reprocessed silicon materials. Li is the largest shareholder at 14%, followed by Hillhouse Capital Management at 5.8%. Longi is currently Hillhouse’s largest disclosed position worth $4 billion, an encouraging seal of approval coming from arguably the world’s most successful institutional investor in the Chinese markets.

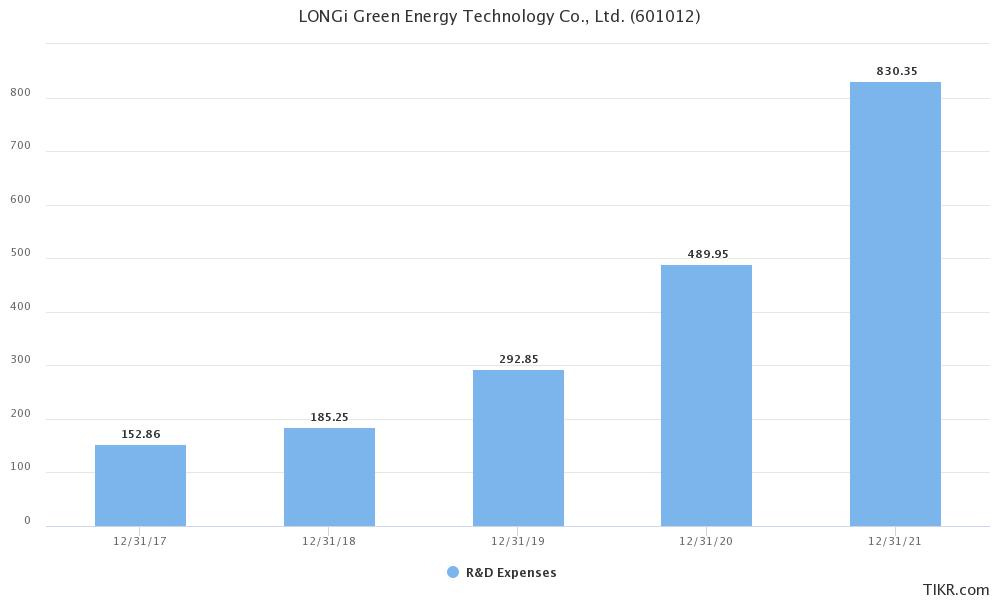

Longi’s entrepreneurial DNA is evident in its company history, first pivoting from supplying the semiconductor industry to the emerging solar industry to eventually dominate monocrystalline ingot and wafer production, then shrewdly acquiring Lerri Solar in 2014 to enter the cell and module business. R&D investments are ramping exponentially along with profits, with a view toward entering new markets like building-integrated photovoltaics and power-charging stations for electric vehicles, as well as long-term ideas that may become viable as the cost of solar declines, such as green hydrogen production or water desalination for desert irrigation connected to solar farms.

Tectonic shifts in geopolitics

If the exponential growth of these industries ultimately leads to the total disruption of the legacy energy and transportation markets, this will have a major impact on geopolitics. With a dominant share in many of the key technologies needed for the transition, China is poised to be a big winner, and many countries will rely on Chinese companies to build out their energy infrastructure. However, this will not be a zero-sum game. When Tesla buys Longi panels to power a new factory in the United States, who benefits the most in the long run? Longi, owned by private individuals and institutions representing both Chinese and foreign investors, gains a one-time net profit of 10%, while Tesla earns much more in reduced energy costs over the lifetime of the panels. On the other hand, when the U.S. imports oil from Saudi Arabia, Saudi Aramco (95% government-owned) takes a 50% profit, the oil is quickly consumed and needs to be purchased over and over again. The Saudi Arabian government’s outsized influence over global oil supply causes many other governments to turn a blind eye to human rights violations in the country.

Unlike oil production, manufacturing operations can be relocated and supply chains can be adjusted as needed to address trade conflicts. Countries do have some power to affect change within China through trade policy; however, the tools at their disposal are blunt and may not have the exact impact desired. For instance, the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act bans all goods from the region, which produces about half of the world's polysilicon, unless importers can prove they were not made with forced labor. While the supply chain appears to have adjusted to exclude a supplier that was a target of forced labor allegations, complexity and a lack of transparency within the country pose significant challenges to ensuring the regulations are met. Likewise, U.S. tariffs imposed on Chinese solar panels with the stated intention of supporting domestic production have simply encouraged Chinese manufacturers to move production bases for final assembly to Southeast Asia. New tariffs on production coming from Southeast Asia is likely to have a similar impact. Notably, the higher-value bifacial panels that Longi specializes in are exempt from U.S. tariffs.

Investor Takeaway

Longi is a case study on how to successfully execute a vertical integration strategy. Longi started by focusing on niche markets (monocrystalline wafers, bifacial modules) that eventually became the mass markets as the Company drove costs down. Once Longi held a dominant share of the critical input to cell production, there was not much resistance to their push into cells and modules, as the competition was fragmented and financially weaker. Vertical integration is a relatively difficult and costly strategy to pursue, but once successful it can be the source of a durable competitive advantage.

I am finding parallels with emerging winners in the Chinese wind and battery space as well, which I plan to cover in future posts. If you have found this informative or thought-provoking, please share it with your network and stay tuned!